In February 2019, I found myself just outside of Atlanta in a low-rise industrial office building, waiting for Kevin Nolan. An investment banker with a specialty in the logistics industry had introduced me to Nolan, saying that, among the new generation of fast-growing freight brokerage businesses, Nolan Transportation Group was the “real deal.” As I walked through NTG’s office, past the empty beer kegs adorned with SEC school flags, I saw a small army of 20-something year-olds talking frantically into their headsets over Metallica blaring overhead. Nolan, a huge man with an equally large presence, was their chain-smoking leader.

A freight brokerage connects any business (the shipper) with a third-party trucking company (the carrier) to move their goods over the road. In the United States, over 70% of freight by weight is moved by a fleet of about four million Class 8[1] trucks. Roughly half of these assets are owned by companies that use them to move their own freight, e.g. Pepsi and Walmart have huge fleets of trucks they own and operate. The balance, carriers who move freight for external customers, comprise the “for-hire” truckload market which earns about $400 billion in revenue each year. This is a highly fragmented industry: over 70% of registered carriers own fewer than three trucks.

The freight brokerage industry, which functionally came into existence through the deregulation of the trucking industry in the 1980’s, creates value by aggregating the highly fragmented supply in the carrier market and matching it with the demand from shippers. Freight brokerage penetration of the for-hire truckload market has roughly doubled in the last 15 years yet is still only somewhere between 25-30% (in 2021, XPO estimated ~$90bn of Gross Revenue in the brokered truckload industry)[2]. This has been an industry with an exciting growth trajectory: as penetration has increased, aggregate revenue has grown at a low-teens clip for the past twenty years. The freight brokerage industry itself is also fragmented: the biggest freight brokerage has about 10% market share and the top 50-companies control about 60% of the market with a long tail of smaller businesses.

Let’s look at how we got here.

The first truck powered by internal combustion was designed and built in 1896 by Gottlieb Daimler in Germany. Eighteen years later, in 1914, August Fruehauf, a Prussian immigrant to Detroit, MI, invented semi-trailers and, following engineering improvements to the axle and chassis, truck transportation took off around the world. For example, in 1920, motor carriers transported less than 1.0% of the intercity freight in the United States. By 1939, this had increased to 19.2%[3].

After industrial activity in the United States plummeted in the Great Depression, there were too many trucks competing for too little freight. The excess capacity drove freight rates below cost and created safety problems as trucking companies pushed their drivers to the limit and skimped on vehicle maintenance[4]. Hundreds of trucking companies filed for bankruptcy and, as part of the New Deal reforms, the Roosevelt administration and Congress passed the Motor Carrier Act of 1935. It allowed the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) to regulate the entry, rates, and safety of trucks and buses across the country.

Calls for regulatory reform grew in the late 1950s, especially ICC regulated rate bureaus, which were exempt from the price-fixing statutes of the Sherman Antitrust Act. As the use of truck transportation took share from rail following the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956, it increasingly became consensus that the ICC micromanaged monopoly system was a net-negative for the US economy. This became top-of-mind for the public when the trucking industry was increasingly linked with organized crime and colorful characters like Jimmy Hoffa and the Genovese crime family.

President Jimmy Carter made it a top priority to deregulate transportation. The Motor Carrier Act of 1980 (MCA) was the beginning of deregulation in the trucking industry and the start of a new era in transportation. Trucking companies were given authority to set rates independently, and most antitrust immunity for collective rate-making was eliminated[5].

As a result, existing carriers expanded into new services with new routes and new carriers entered the business. Deregulation also increased the use of owner-operators, drivers who own their own vehicle and typically “rented themselves out” to larger carriers. In the years immediately following 1980, the use of private carriers ("in-house" trucking fleets) declined considerably and the number of carriers exploded. In 1975[6] there were 18,000 trucking companies in the US. As of 2020 there were ~750,000 carriers with active DOT Numbers[7]. The MCA also allowed for the introduction of independent freight brokerage.

Following deregulation, freight brokers had a bad rap. As a journal article described “the industry has been inundated with undercapitalized, fly-by-night brokers who are preying on unsuspecting carriers and shippers”[8] This followed from an extraordinarily low regulatory barrier to entry: a simple ICC application with a $10,000 bond[9] was sufficient to start calling up shippers for loads.

A company out of Chicago, American Backhaulers, changed the game. Founded just after deregulation, Backhaulers was led by Paul Loeb & Jeff Silver who sought to professionalize the business. One innovation that drove Backhaulers’ success was following a novel business model—instead of having freight brokers handle the entire transaction from sales to delivery, they split employees up into teams that would focus on individual parts of the brokerage process (customer sales, carrier sales, operations, etc.)—later dubbed the “Chicago Model,” (in contrast to the “cradle-to-grave” model). The Chicago Model allowed Backhaulers to handle larger corporate customers with higher load volumes, maximizing efficiency in terms of loads per broker per day. They also developed software that would be the predecessor to the modern transportation management system (“TMS”) which functions like a CRM with functionality to match customer loads with carrier trucks. Loeb & Silver led an incredible culture of excellence—Backhaulers alums have been incidental in the creation or growth of nearly every successful freight brokerage businesses since.

In 1999, C.H. Robinson, a publicly traded transportation company, acquired Backhaulers for $136 million in a landmark deal. CH Robinson remains the largest brokerage business in the US today, with $12.4bn in gross revenue generated from freight brokerage in 2023. Loeb and Silver left Backhaulers[10] following the acquisition. Loeb went on to found Command Transportation (sold to Echo Global in 2015 for $420mm) and Silver teamed up with Warburg Pincus to build Coyote Logistics.

Coyote quickly became an important company in the brokerage world. Instituting a rigorous training program to scale young talent, Coyote excelled at handling corporate accounts, particularly on the carrier operations side, working with mid-size trucking companies to “wholesale” freight efficiently. Their access to private equity dollars also allowed them to absorb the working capital burden of their aggressive growth trajectory. The success was also very much an extension of its founder— multiple people I’ve spoken to have likened Jeff Silver to a Logan Roy-esque character. People have described the culture as win-at-all-costs, which included everything from excellence in carrier sales to communal bowls of Adderall. A former Coyote employee told me that he “joined the company out of high school and two weeks in, he didn’t know who CH Robinson was, but he wanted to kill him.” UPS acquired Coyote in 2015 for $1.8b in another important transaction. Like Backhaulers, Coyote alums proliferate the brokerage world today.

The home-run for Warburg increased interest from private equity, which was reinforced by a change in lender perception that the enterprise value (and high quality accounts receivable) of a freight brokerage business were just as credit-worthy as the hard assets of a regular trucking business. To PE, the idea was: (1) freight brokerage was attractive from a recurring revenue and return on capital perspective; (2) consolidation in the industry will go on for the foreseeable future, with attractive M&A economics; And, (3) there was an explosion of software businesses making logistics more efficient and those who implement the right tech stack will likely be able to grow faster than the industry.

To understand the economics of this business, let’s back up for a minute: A brokerage business earns revenue by placing loads with carriers and taking a spread. Loads are won from shippers on a spot basis or via an RFP process for a set number of loads over a 6–12-month contract period. On a standard dry van truckload, margins are normally anywhere from 8-15% depending on the market environment and kind of shipper (e.g. large enterprise contract freight vs. SME customer spot).

The relative profitability and quality of a brokerage business are not just driven by scale: mix is important too. Dry-van, referring to a tractor with an enclosed semi-trailer, is the most common way to ship freight, and therefore most commodity-like. Other more specialized lines of freight include refrigerated (“reefer”), flatbed, or other specialized trucks/loads. For brokers, aside from cultivating more unique shipper and carrier relationships, this specialization is a matter of “speaking the language” of the two sides of the market and brokers indeed tend to specialize.

There are many different flavors of operating-model but a freight brokerage’s biggest cost is typically payroll and commission expense. Tech costs (software subscriptions and internal development) and office rent are also material. A brokerage business earning >$200mm of Gross Revenue should be able to earn 5% EBITDA margins, unless they’re trying to grow very quickly and will have a productivity drag on earnings—many players of this size or greater eschew profitability to invest in growth by ramping headcount.

Despite being referred to as “asset light,” brokerage businesses are effectively long the AR of their shipper customers, which is deceptively asset intensive. Freight factoring has grown alongside brokerage over the last decade and many brokerages sacrifice anywhere from 2-4% of gross revenue to avoid holding excess amounts of working capital—in comparison to 5% EBITDA margins, this is a big deal. In an interview, Kevin Nolan described his early days of struggling with working capital:

“Our best collections tactic was I would take a black marker and I would make the page as black as I could and I would fax it to the shipper 100 times and I'd call him and say, hey, I'm going to eat all your toner.(...) That's expensive. Hell yeah it was. It was a black fax.”

Life as a freight broker is tough and people in the industry work really hard. It’s not uncommon to start out making 100+ cold calls a day to shippers. Aside from the abstract concept of “aggregating supply in the highly fractured carrier market,” because freight is a commodity, brokers get paid for service, i.e. dealing with problems. These issues range from dealing with incompetence, to fraud, to Acts of God[11] and I’ve heard many stories of freight brokers doing anything to get the job done: from sleeping with their phones on their chest, to trying to recover stolen trailers from the Serbian mob in Chicago. Every seasoned freight broker seems to have “the story.”

Broker turnover is relatively high and brokers are frequently jumping ship to start their own businesses. If you have good client relationships, splitting off, hiring one or two people, and creating a nice lifestyle business[12], is something that is reasonably achievable. Scaling that business into something larger and investing in a competitive advantage is relatively hard, however.

One of the most difficult parts of scaling a brokerage is managing the business through the freight cycle. Because of the highly fractured nature of the market, relatively small mismatches in supply-and-demand cause dramatic changes in rates—for every broader macro-economic cycle, there seems to be two or three freight cycles of varying magnitudes. As payroll is a typical brokerage’s biggest fixed cost, the cycle creates a real challenge in terms of hiring, training and scaling. When the cycle turns down, brokerages are forced to lay off their least short-term productive employees: brokers who are still learning the business and developing relationships, and are left short of manpower when the cycle turns up-- the best brokerages can retain and expand their talent pool in a counter-cyclical way.

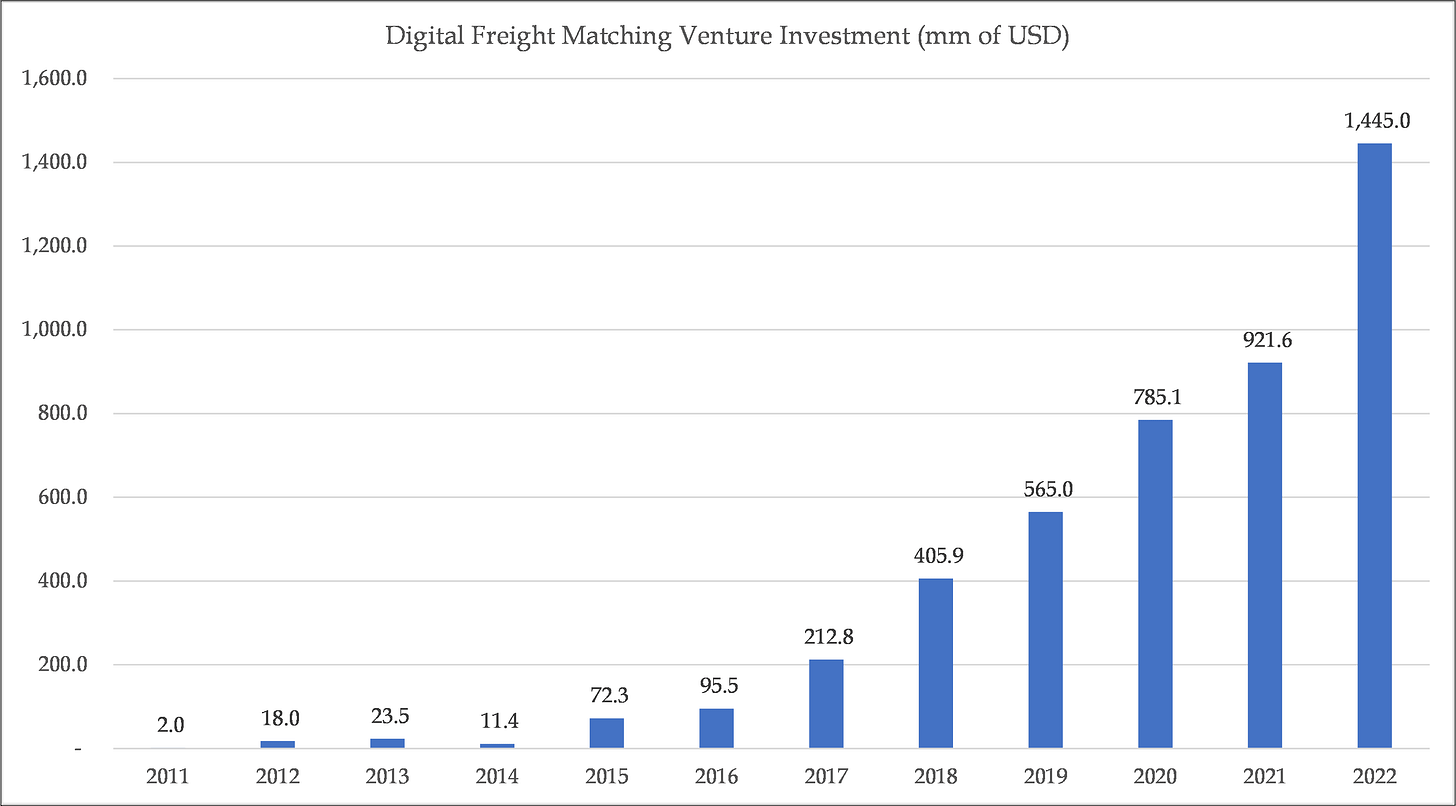

In addition to Private Equity, starting in 2013-2014, the VC world became very interested in freight. Specifically, interest was piqued by the intuitively appealing idea of “Uber-for-Trucking,” and so-called “Digital Freight Matching” businesses started raising a ton of money. Founders raising money promised investors that their easy-to-use APIs and freight-matching algorithms would disrupt an antiquated market. Specifically, there was a massive capacity inefficiency, as ~25% of backhaul trips were run without loads—technology would solve that inefficiency. Fundraising exploded into the ZIRP-craziness of the last decade:

While the majority of VC dollars went to DFM start-ups like Convoy, Transfix and Flexport, the most valuable innovation has happened around building on top of the TMS. A typical software architecture looks something like this:

All of this innovation focused not on making the broker obsolete, as per the implicit threat of the DFM, but making the brokerage process more efficient: increasing the loads per broker per day as the most important velocity metric. You can break these software solutions into various buckets: automating pricing for the shipper, allowing for the constant monitoring and prediction of carrier capacity, instant app-based booking loads for the carrier, real-time load tracking; integrating an API-based network for both the shipper and carrier, automating back-office functions like carrier onboarding, freight bill audit and payment, etc.

While some of these were developed internally at the DFMs, they were and are more commonly developed by third parties and used by brokerages via license. The distinction between a digital freight matching business and a traditional brokerage embracing the new technology tools looks increasingly meaningless[13]. Uber themselves started their own DFM, and then went onto acquire Transplace, a brokerage owned by TPG (and is now a top-5 brokerage in the US).

The theory goes: by booking more loads per broker per day[14], brokerages can earn lower per-load net revenue margins but higher EBITDA margins at scale and take significant market share from less efficient players. This is effectively the escape velocity with respect to a scale advantage the industry has yet to really see materialize. One tech-inclined brokerage CEO painted the picture that, just how Backhaulers changed the industry, we would see a new level of productivity shape the industry.

The market conditions brought on by COVID lit a flame under the growth. The increase in freight demand as US consumption shifted towards ecommerce, coupled with disruptions in the supply chain, led to a historically strong rate environment. Brokerage businesses were not only suddenly printing money, but because interest rates were close to zero, they could carry the working capital pretty cheaply and most were reinvesting their cash flow to grow rapidly.

The brokerage business most emblematic of this period was perhaps MoLo Solutions. MoLo was led by Andrew Silver[15], who now hosts the best podcast on the industry, The Freight Pod. Silver and his team set out to be the gold standard deploying the Chicago model aggressively. The growth was ridiculous: MoLo grew from $5 million in revenue in 2017 to $625 million in 2021 and sold out to ArcBest for $235 million.

Given strong load margins, interest from VC and PE capital with a focus on growth-at-all-costs encouraged by low-cost debt financing, lots of new brokerages set up shop in the last ten years. Essentially any market share consolidation was tempered by new business formation:

Then, in late 2022, the biggest bull-market in freight reversed.

The high freight rates of COVID encouraged carriers to add supply in an unprecedented way, leading to massive truckload overcapacity and, as ecommerce demand corrected back-to-trend, demand for over-the-road transportation stagnated. Load margins crashed and increases in interest rates caused a spike in debt financing and factoring costs. Shippers also stretched their accounts payable, exacerbating the net working capital needs of brokerages. To illustrate the effects on profitability, if your brokerage was generating $5mm in EBITDA off $100mm of revenue, given a slight contraction in load volumes and a contraction in rates, a decrease in margins and an increase in factoring costs, all your EBITDA goes away.

Suddenly, if you had generated any cash in 2022, that was needed to keep the lights on. Many had reinvested that cash in growth and many owners of smaller brokerages had personally guaranteed a bank line to fund working capital – they were looking at personal financial ruin. John Marrinson, Group Head of Tranporation & Logistics at WinTrust Bank, described[16] this perfect storm hitting the market:

The problem that we're seeing is the liquidity is suddenly drying up. And you're not only being hit with a lack of capital, but you're also being hit with margins that are being squeezed for various reasons. (...) Traditional brokerage is very scalable, both up and down. You know, it's not pleasant sometimes in a down market because typically how you scale back is by cutting heads and reducing your overhead. But when you've got fixed costs, it's a different game.

The bigger issue right now is with interest rates increasing significantly. Those fixed costs that, you know, 12 months ago, were "X" are now two times "X," because your variable interest rate on your working capital facility is now costing you more dollars in a time where your margins are getting squeezed.

One of the first levers that a broker is going to pull to help their cash flow is extending their payable terms with their carriers. And that's, you know, not only is that a concern from the carrier side, but more importantly, the carriers, to a large extent, work with factorers. And the factorers are the ones now saying, okay, well, wait a minute, why is broker A paying me in 43 days now when it's been 35 days for the past three years. And that's where we start to see that the problem on the credit side come through, where the credit insurance companies are pulling back from the freight market.

And the first place that they do that is the credit lines that they're willing to hold on brokerages. Even significantly large brokerage, if they're private, and there's no visibility into their financials, credit insurance companies are going to pull those lines. And I've talked to four or five clients in the past two weeks that are all telling me exactly that. So, then that creates a problem with the factorer relationship, because their historical carrier network is now saying, well, I don't know if I can pick up that load because my factorers saying they won't carry your receivable anymore. So, that liquidity change and credit availability in the marketplace is what is going to accelerate the reduction in capacity as it relates to both the carrier and broker side.

Large shippers historically have always considered transportation a 30-day payable. They're now realizing, hey, wait a minute, just like we work with our vendors, we're pushing all of them to 60, 90 days. That has a big impact. And again, exacerbated by increased interest rates with your working capital costs. So, we've kind of got this perfect storm of not only a down cycle in the industry, which obviously has happened before, but there's a big change in the relationship between shippers, carriers, brokers.

As the Buffett-ism goes “only when the tide goes out do you discover who's been swimming naked.” One interesting ramification was that we saw a number of fast-growing technology-enabled-brokers being exposed—they weren’t being managed with the cycle in mind, their “proprietary” tech stack wasn’t really valued by shippers and they were simply underpricing the market to steal share. There have been a few high profile blow-ups, most notably Convoy in October 2023.

Seeing the cycle turning, beginning in 2023, I ran all over the country trying to find a freight brokerage business to acquire. I met with different kinds of targets in terms of size, business model, geographic focus, performance through the crisis, etc. I kept encountering a negative selection bias: the businesses that needed cash were often subscale operators trying to grow aggressively using the Chicago model, in effect with broken businesses. These brokerage businesses often had significant customer concentration with one or two large enterprise shippers, who in effect were squeezing them in terms of load volumes, margins and working capital. In some cases, brokerages had locked in significant contract freight at much higher rates and therefore had overinflated margins, as they were benefitting from being “short” carrier capacity—when the cycle turned, EBITDA growth would be tempered.

The few brokerages that were outperforming the depressed market were still clinging to valuations from ZIRP-land or just wanted to wait until the market was good to sell. I would still really love to find the right business or management team to partner with (please reach out!). I’m increasingly convinced that scaling a brokerage inside of an integrated 3PL ecosystem following an “asset-right” strategy is the way to go (particularly with drayage, transload and other warehouse services).

The pain in the industry continues today and the market is actively consolidating. Kevin Hill at Brush Pass Research tracks FMCSA registrations:

According to Hill, “YoY declines in active freight brokerages have accelerated downward each month in 2024. Starting in January at (7.8%), reaching double digits in April, and now at (11.6%). 2-year declines are now at (12.4%) and a 3-year comparision is almost flat at 1.4%. There are now 26,653 active freight brokerages compared to 31,235 at the height in Nov 22.”

Aside from the contraction in debt and equity capital available to start new brokerages, the ownership composition of the largest players in the industry portends further consolidation. Thirteen of the top twenty freight brokerage businesses are either owned by private equity (mostly acquired within the last five years), or are themselves acquisitive, or out-of-business, in the case of Convoy:

Many brokerages will either close shop, be acquired by other brokers or join asset-based businesses.

On Sunday, June, 23, 2024, the biggest consolidation news story (yet) hit the wire: RXO announced they would acquire Coyote Logistics from UPS for $1.025 billion. In 2022, RXO was spun-out of XPO, the publicly traded multi-modal logistics company run by Brad Jacobs. I won’t go into Brad’s background or track record here, but the record is phenomenal[17]. Drew Wilkerson is the CEO of RXO, Wilkerson is a former CH Robinson guy who rose through the very demanding management culture at XPO before Jacobs appointed him CEO of the brokerage centric business.

The origins of RXO trace back to the business that existed prior to Jacobs’ involvement, Express-1. Originally, Jacobs was focused on asset-light businesses before expanding into LTL through M&A. RXO is also not just freight brokerage, which was about 60% of the business from a revenue perspective in 2023.

About 25% of the topline in 2023 came from “Last Mile” revenue. XPO acquired this business in 2013, at the time called 3PD, for $365mm at 10X EBITDA—today the business does >$1bn in annual revenue. Aside from the impressive headline numbers, I get the sense that there aren’t a lot of assets like that in the space, likely giving it some scarcity value premium.

About 11% of revenue comes from Managed Transportation, where RXO takes over a shipper’s whole slate of relationships with multiple 3PLs, optimizing the customer’s overall transportation spend—a business with a different type of sales-cycle and customer stickiness also one that typically commands a higher multiple than brokerage in the private market.

Pretty much all of RXO’s growth has been organic historically. At the time of spinoff in 2022, RXO’s Form 10 showed that the business grew truckload revenue by 27% GAGR from 2013-2021. Revenue growth was a bit better-than-flat in 2022 and, in 2023, RXO’s overall revenue was down -18.1% y/y. This was primarily driven by truck brokerage down -19.5% y/y, which was better than the overall market but not amazingly so. Last Mile and Managed Trans performed better.

RXO’s EBITDA margin was 3.2% in 2023 which, considering the business mix and size, is a bit low and reflects a fantastic amount of investment in technology. Some of this is also capitalized on the cash flow statement—so there wasn’t much actual FCF in 2023.

Once the transaction with Coyote is closed, RXO will become the third largest freight brokerage business in North America (surpassed by CH Robinson[18] and TQL). On the M&A call following the announcement, Wilkerson noted “there is minimal overlap across our largest customers,” which was surprising. I would have guessed that the biggest short-term risk of to the deal was that of customer cannibalization, which is very real in brokerage M&A. There’s also a cultural consideration here: brokers are very territorial about customer relationships and retaining good talent that has to give up part of a book of business is tough. Jacobs’ track record in M&A is great and I would be surprised if they didn’t underwrite this risk extensively.

Coyote’s carrier capacity relationships have historically been more weighted towards mid-sized trucking companies, which opens up RXO’s carrier network. Coyote will also give RXO brokerage businesses in LTL and crossborder[19], which present cross-sell opportunities to RXO’s existing customer base and likewise for RXO’s managed transportation business to Coyote’s customers.

After UPS acquired Coyote, and Silver left the business, there’s been a constant stream of top talent out of the business. Employee turnover at brokerage businesses is normally pretty high but complaints about UPS’ bureaucracy and the lack of strong leadership (which might just be true in comparison to Silver) were common refrains. In brokerage businesses, the culture seems to stem directly from the top guy. We’ll have to see if Wilkerson can rise to the occasion.

The headline valuation on the deal is 11.9x 2023 adjusted EBITDA before synergies and 9.2x after synergies, which is a fair multiple on cyclically depressed earnings—so fairly attractive. The company is raising $550mm in equity, with the balance in debt.

Here’s a simple back of the excel/envelope math to frame valuation:

Starting from PF 2023 combined revenue, we can model a 5-year CAGR range of 7.5-17.5%. At the low-end, this implies some combination of market saturation, material customer losses from poor M&A integration and/or a persistently weak rates environment (particularly weak considering where we currently are in the cycle). At the high end, it assumes a modest annual premium to historical industry growth.

In terms of profitability, at the low end, assuming a 3.5% EBITDA margin implies there’s little leverage gained on tech spend or broker productivity and/or industry margins contract because of increased competition. At the high end, 5.5% would be in-line with full-cycle historical profitability.

Considering a robust historical comp set, I feel relatively comfortable valuing RXO at 10-12X EBITDA. Adding in some modest share dilution and discounting any accumulation of FCF over the next five years, downside is $22 per share, implying 20% downside from today’s price of $26.79 per share. At the high-end, which seems like a reasonable outcome, you triple your money over five years.

What is the end-game for RXO? Will they be consolidated or be the consolidator? Jacobs is a rational steward of capital but a lot will be determined by how well the integration of Coyote goes. At what size will we see self-reinforcing returns to scale in freight brokerage? Will there be a freight brokerage market where the top-10 players have 80%+ market share? It’s happened in other transportation segments like LTL trucking and rail, but those advantages were driven by the configuration of physical assets. There could be an analogy in that brokerages may come to dominate carrier supply in certain “trade lanes.” Could value creation through scale advantages drive brokerage penetration >60%, and even expand the reach of the for-hire OTR market? I don’t know that anyone has high-confidence answers to these questions but a range of possibilities skew positively for RXO 0.00%↑.

[1] These are the big 18-wheelers you see on the highway.

[2] These numbers are somewhat disputed as different definitions include/exclude brokerage associated with larger asset-owning transportation companies. Armstrong & Associates, for instance pegs 2021 Total Domestic Transportation Management Gross Revenue at $139bn, implying penetration maybe higher. XPO/RXO clearly has an incentive to paint the market as less-penetrated.

[3] Marco Poisler and Edward D. Greenberg, History of Trucking Regulation: 1935 to 1980, Transportation Lawyers Association

[4] Trucks are still incredibly dangerous. In 2019, there were approximately 6.7mm motor vehicle accidents in the United States. About half a million involved large trucks. Keep in mind that there are only 4mm trucks vs. ~275mm registered vehicles overall.

[5] The federal government later removed intrastate regulations in 1994.

[6] Bureau of Transportation Statistics

[7] Appx. 600k of these are owner-operators. Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration Pocket Guide to Large Truck and Bus Statistics 2022

[8] Motor Freight Brokers: A Tale of Federal Regulatory Pandemonium, Northwestern Journal of International Law & Business

[9] Today licensing is similarly laissez faire through the FMSCA

[11] For an endless supply of these stories and a window into the industry culture r/freightbrokers is a good source.

[12] I’ve met several guys in their 30s who have purportedly net >$1mm in a single year doing this. So, “lifestyle business” is kind of an understatement.

[13] A discussion of load boards, both internal and external, is probably appropriate here, but beyond the scope of this essay.

[14] In addition to broker load count, we can measure the level of technologically enabled efficiency by looking at metrics like carrier reutilization (loads per “A” carrier per month), percentage of freight real-time tracked, percentage of digital booking, freight bills processed, etc.

[15] Andrew also happens to be Jeff’s son. A recommended listen would be his interview with MoLo cofounder, Matt Vogrich. Andrew’s brother Matt also founded an exciting startup called Cargado, which is creating a software platform for US-Mexico crossborder freight

[16] The Freight Pod, Oct. 24, 2023

[17] Jacobs has been on a media tour over the last year, coinciding with the release of his book, How to Make a Few Billion Dollars. I would recommend.

[18] Which has its own issues beyond the scope of this essay.

Hi James - May I ask where you got the market share data from? This was a very helpful read for someone trying to understand the freight broker market better. Thanks!